BACKGROUND TO THE DISPUTE

On 14 June 2017, Mr Hamid Ahmad Chakari, filed an application for registration of an EU trade mark with the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO).

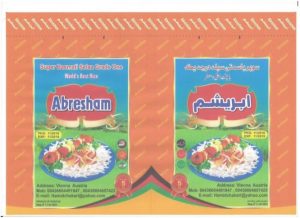

Registration as a mark was sought for the following figurative sign:

The goods in respect of which registration was sought fall within Classes 30 and 31 of the Nice Agreement: Class 30: ‘Flour of rice; rice-based snack food; rice cakes; rice pulp for culinary purposes; extruded food products made of rice´ and Class 31: ‘Rice meal for forage’.

The appellant, Indo European Foods Ltd, filed a notice of opposition pursuant to Article 46 of Regulation No 2017/1001. The opposition brought by the appellant was based on the earlier non-registered word mark in the United Kingdom BASMATI, used to refer to rice. The ground relied on in support of the opposition was that referred to in Article 8(4) of Regulation 2017/1001. The appellant argued, in essence, that it was entitled under the applicable law in the United Kingdom to prevent, by means of the ‘extended’ form of the action of passing off.

The Opposition Division rejected the opposition in its entirety. It found that the evidence submitted by the appellant was insufficient to prove that the earlier mark had been used in the course of trade of more than mere local significance prior before the relevant date and in the relevant territory. Consequently, according to the Opposition Division, one of the conditions set out in Article 8(4) of Regulation 2017/1001 was not satisfied.

On 16 May of the same year, the applicant filed an appeal against the Opposition Division’s decision with EUIPO. The Fourth Board of Appeal of EUIPO dismissed the appeal as unfounded, on the ground that the Appellant had not demonstrated that the term ‘basmati’ enabled it to prohibit the use of the mark applied for in the United Kingdom by virtue of the unlawful act of passing off at common law.

According to the evidence submitted by the applicant, in order for an action to be successful under that tort, it must be shown that, first, the name ‘basmati’ denotes a clearly defined class of goods; secondly, that name has a reputation giving rise to goodwill amongst a significant section of the UK public; thirdly, the applicant is one of many traders entitled to rely upon the goodwill associated with that name; fourthly, there is a misrepresentation by the trade mark applicant leading or likely to lead the public to believe that the goods offered under the contested sign are ‘basmati’ rice; and fifthly, the applicant has suffered or is likely to suffer damage as a result of the erroneous belief engendered by that misrepresentation.

The Board of Appeal found that the first three conditions of the extended form of passing off were met. By contrast, it found that the applicant had failed to demonstrate that the use of the sign whose registration was disputed could result in a misrepresentation of the reputed name ‘basmati’. Furthermore, the Board of Appeal took the view that, in the present case, use of the mark applied for could not cause a direct loss of sales for the applicant, since the contested goods were goods other than rice, whereas the applicant sold only rice. Likewise, there was no argument to explain how use of the mark applied for could affect the distinctiveness of the name ‘basmati’, taking into account that ‘super basmati’ was a recognised variety of basmati rice.

DECISION OF THE GENERAL COURT

The action for annulment

By virtue of Article 8(4) of Regulation No 207/2009, the proprietor of a non-registered trade mark or of a sign other than a trade mark may oppose the registration of an EU trade mark under the following four conditions: (i) the sign is used in the course of trade; (ii) it is of more than mere local significance; (iii) rights to the sign have been acquired prior to the date of application for registration of the EU trade mark; and (iv) the sign confers on its proprietor the right to prohibit the use of a subsequent trade mark. Those conditions are cumulative; thus, where a non-registered trade mark or a sign does not satisfy one of those conditions, the opposition based on the existence of a non-registered trade mark or of another sign used in the course of trade within the meaning of Article 8(4) of Regulation No 207/2009 cannot succeed.

In accordance with Article 95(1) of Regulation 2017/1001, the burden of proving that the condition according to which the sign confers on its proprietor the right to prohibit the use of a subsequent trade mark is satisfied lies with the opponent before EUIPO (see judgment of 23 May 2019, Dentsply De Trey v EUIPO – IDS (AQUAPRINT), T‑312/18, not published, EU:T:2019:358, paragraph 100 and the case-law cited). Since the judicial review conducted by the Court must meet the requirements of the principle of effective judicial protection, the examination carried out by the Court under Article 8(4) of Regulation No 207/2009 constitutes a full review of legality.

The applicant’s opposition is based on the extended form of passing off available under the law applicable in the United Kingdom. The appellant refers to the Trade Marks Act 1994, section 5(4) of which provides, inter alia, that a trade mark may not be registered if, or to the extent that, its use in the United Kingdom may be prevented by reason of any rule of law (in particular, under the law of passing off) protecting an unregistered trade mark or any other sign used in the course of trade. It follows from section 5(4) of the United Kingdom Trade Marks Act that the party relying on it must prove that three conditions are satisfied: first, that the sign in question has acquired goodwill; second, that the offering under that sign of the goods covered by the later mark constitutes a misrepresentation by the proprietor of that mark; and, third, that there is detriment to the goodwill.

– On misrepresentation

Therefore, even if the goodwill attaching to the name ‘basmati’ relates only to basmati rice, as a variety or class of goods, by reference to the Basmati Bus decision, a non-negligible part of the relevant public might believe that the goods referred to by the Board of Appeal, namely flour of rice, rice-based snack food, rice pulp or rice meal for forage, labelled ‘Abresham Super Basmati Selaa Grade One World’s Best Rice’, are in some way associated with basmati rice. Thus, the applicant is correct to claim that the relevant public would expect, when purchasing a product that is stated to be, contain or be made from basmati rice, that that product does indeed contain that rice.

Furthermore, as regards the Board of Appeal’s finding that the applicant did not claim, let alone prove, that the mark applied for was used in the United Kingdom and that such use occurs for goods not made from genuine basmati rice, it must be noted that the actual use of the mark applied for is not one of the conditions for an action for passing off. It is apparent from the decision of the Court of Appeal (England & Wales) that a notional and fair use of the trade mark applied for must be presumed.

– The damage

The applicant argues that damage to the goodwill in the name ‘basmati’ is liable to arise if foodstuffs thought to be made from basmati rice are in fact made from another type of rice, and submits that the damage arises from the loss of distinctiveness or the ‘very singularity and exclusiveness’ of genuine basmati rice. According to the applicant, the Board of Appeal’s assertion that there is no argument of how use of the mark applied for could affect the distinctiveness of that name, on the basis that ‘super basmati’ is a recognised variety of basmati rice, is not relevant since that assertion presupposes that such mark is used for goods made from basmati rice.

Furthermore, since the Board of Appeal noted that there was no argument to explain how the use of the mark applied for could affect the distinctiveness of the word ‘basmati’, given that the ‘super basmati’ variety is a recognised variety of basmati rice, that finding proceeds on the false premiss that the use of that mark is limited to goods made from basmati rice or super basmati rice. The likelihood of misrepresentation stems, as stated in paragraph 64 above, from a notional and fair use of that mark in the light of the general description of the contested goods, namely goods based on a wide range of rice varieties.

In view of the foregoing, the applicant’s single plea in law must be upheld and, consequently, the contested decision must be annulled.

Español

Español Deutsch

Deutsch